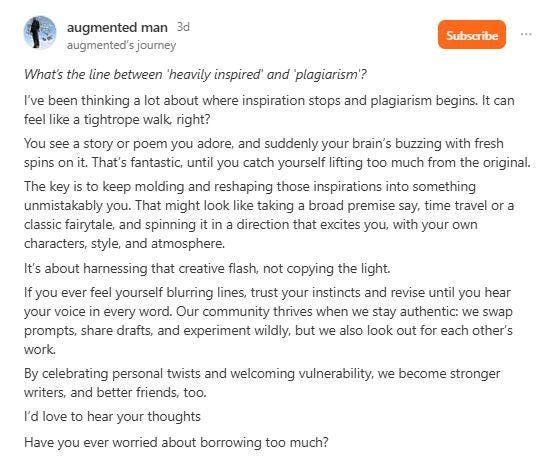

The above was an inquiry/statement by the user Augmented Man that was posted last week. I think the issue of inspiration versus plagiarism, or originality versus the derivative, is a topic of great concern. In fact, it may very well be the grand issue, the great divider, the absolute question—as technology provides more and more the capacity to manufact…